A review of Smartphones and Close Relationships: The Case for an Evolutionary Mismatch

The short answer is sort of. It is more a matter of them feeling that you’re picking your phone over them when you think you’re just splitting your time.

I’ve been thinking about this question for a long time. Regularly wondering how I waste so much time after scrolling on any number of apps or websites on my phone. Then I feel guilty about how I could have spent that time with my girlfriend or close friend, etc., etc.

I’ve tried many tricks from deleting the Instagram and Facebook apps to setting “times” when smartphone use is acceptable. There were two massive flaws with this plan:

- I can go to my chrome app (which has all my passwords saved) and go to Instagram.com or Facebook.com.

- Personally controlling my screentime has a major point of failure. The person (me).

So What is the Best Solution?

To answer that, we need to really understand the nuances of why we love our phones so much….

A researcher that I had the pleasure of meeting at the University of Arizona, David A. Sbarra, PhD, did a great study with his colleagues on the way that smartphones impact our interpersonal relationships. The study is Smartphones and Close Relationships: The Case for an Evolutionary Mismatch. The study was written by David A. Sbarra, Julia L. Briskin, and Richard B. Slatcher.

This study, like most research, builds on previous work. I am not going to dive into all of these awesome studies. Though I have cited this paper at the end of this post, and it does a great job of supporting and explaining all of the previous work that it has built upon.

Let’s dive into some key points that the paper has built upon:

- Attachment Theory: A middle-level evolutionary theory that addresses interpersonal relationships. Specifically, people bond with each other to increase their evolutionary fitness. This bonding is done through both disclosures and responses to those disclosures. In other words, people, evolving in smaller kinship groups, would be more fit (and therefore able to reproduce) by bonding with other members of their kinship groups.

- Middle-level Evolutionary Theory: A theory of evolutionary psychology. It refers to a specific type of evolutionary theory that focuses on a particular area of functioning.

- Technoference: This simply put, the different ways that a smartphone interrupts normal daily social interactions.

- Evolutionary Mismatch: Defined as, “situations in which human adaptations that emerged to foster reproductive and inclusive fitness in ancestral environments become maladaptive in novel contexts that may differentially cue the same adaptations.”

Before I dive into the research, I want to put a little disclaimer: A lot of the points that I am going to lay out will sound like an indictment of technology. And while there are definitely some things that desperately need to change, technology is here to stay. Not only is it here to stay, but it is going to continue to have more and more of an effect on peoples’ lives.

That being said, the question is not to have technology or not? The question is, how do we use technology and not let it use us?

Breakdown of Smartphones and Close Relationships: The Case for an Evolutionary Mismatch.

The authors of this paper begin by putting their research into context. First, it’s stated that 77% of Americans, as of 2018, interact on social networking sites (Smith & Anderson, 2018). Today, that number has jumped to at least 81%. This effectively explains why this research matters in the context of the average person.

After this, and more, contextualization, the authors describe their goal to examine the possible evolutionary mismatch between smartphones and humans. The mismatch is predicated on Attachment Theory. This theory explains that people are predisposed to share and bond with their kinship groups and, therefore would want to do that as much as possible. The mismatch occurs when people begin to damage closer relationships. We are programmed to want to share more so that we strengthen our relationships with those closest to us. Achieving validation from sharing with those less close to us at the expense of those closest to us is problematic. It results in the very programming that developed to help close relationships doing the opposite.

Now, the study dives into how this mismatch can have a negative impact on relationships. The researchers describe the way that this predisposition to share and receive a response can impact a relationship. In much more elegant words, they essentially say that people in close relationships often feel that their partner is choosing their phones over them. Put another way, one or both partners is choosing to share and receive responses from the edges of their social networks, as opposed to the more integral parts.

At this point the study dives into some pretty scary statistics:

- Out of over 2000 adult couples in the US, 1/4th reported that their partner was distracted by their phone while spending time with the other (Lenhart & Duggan, 2014).

- Increasing to 2/5ths when constrained to 18–29-year-olds.

- Another study found that 70% of women claimed that smartphones negatively impacted their relationships (McDaniel & Coyne, 2016, p. 7).

It’s important to note that the study did qualify these statistics, saying that divided attention was nothing new. Even sighting the example that “[it] is not hard to imagine someone becoming upset with his spouse’s incessant reading of the newspaper (or vice versa) while he is trying to explain the frustrations of his workday.”

With the general conflict established, the research goes into what we can really act on… WHY?

The first idea is that we need to dive into what’s called the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptiveness, or EEA. This means that to understand why we are drawn to share with others, we need to understand the environment that shaped us. To summarize the research, having a better ability to connect with others, especially those that a person wasn’t related to, allowed for both more child survival, and more adult survival.

A “[core] intimacy processes: self-disclosure and responsiveness” section follows the EEA section to connect these ideas to the modern world. In this section, the authors relate the ideas about the importance of intimacy to modern humans through the workings of speech. Importantly, somewhere between 30% and 40% of modern speech is used to tell someone about either personal experiences or other intimate relationships (Dunbar, Marriott, & Duncan, 1997; Emler, 1990, 1994; Landis & Burtt, 1924).

In the following sections, the authors dive further into the weeds of the benefits of these self-disclosure and responsiveness benefits in the EEA. This includes everything from benefits in infant responsiveness to partner responsiveness later in life.

Social media used the desire for self-disclosure and responsiveness to incredible effectiveness. Whether by design or by sheer dumb luck, “more than 80% of social-media activity involves simply announcing or broadcasting one’s immediate experiences (Naaman, Boase, & Lai, 2010).” This means that we are hardwired to want to share on social media, as it preys on the desire for self-disclosure. And, if that wasn’t enough, the social media companies added a “like” button. This allows for the response that we are predisposed to want post-disclosure.

A person shares their feelings, then is rewarded with a positive response.

Hell, no wonder, we can’t get off our phones even when we try. It’s part of our code.

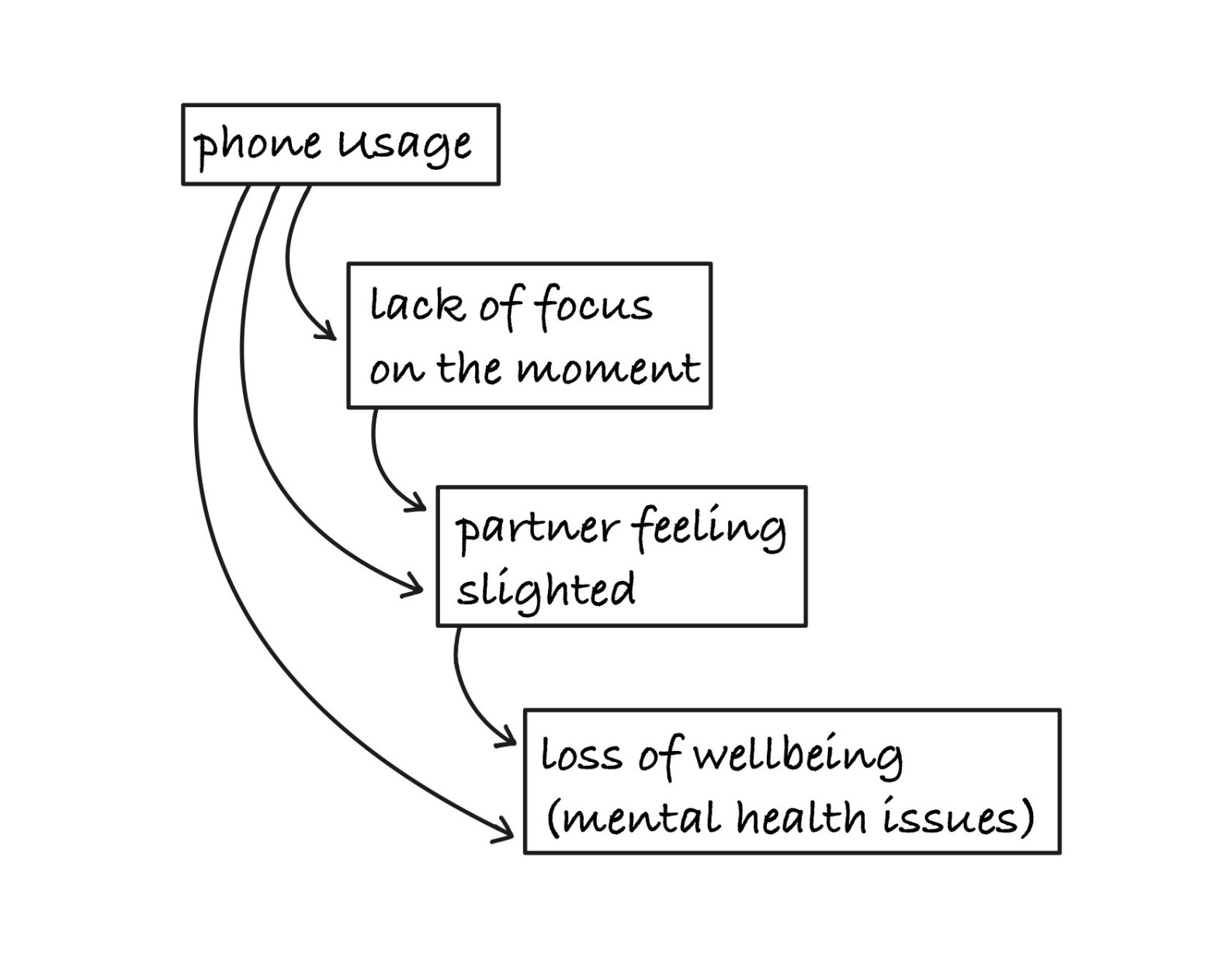

WHY does this susceptibility to smartphones damage our relationships?

In this case, the answer is technoference. Because a smartphone interrupts normal daily social interactions, it can often leave a rift between the phone user and the user on the other side of that social interaction. Smartphones spilt a person’s attention, leading to this effect.

With split attention, we cannot perceive the same number of unusual cues as we normally can (Hyman, Boss, Wise, McKenzie, & Caggiano, 2009). When we miss these social cues, we literally lose parts of the conversation. This is because much of a conversation is nonverbal. For example, in a study of 25 college students, it was shown that when students were involved in a conversation with someone who was using their smartphone, the person on the phone was perceived as less caring because they were less responsive. In that same study, students who were on the phone were less able to hear and focus on the conversation (Aagaard, 2016).

A quick aside: the use of a smartphone while not paying attention to your conversation partner has a term. Phubbing. Here’s a good article on the topic, by the Time.

It’s clear that smartphone usage damages the ability of two people to share and bond to the fullest. The authors then go on to further explain that, not only does the use of a cell phone damage bonding, but the “mere-presence” of a smartphone does the same.

Towards the end of the paper, the authors are clear to point out that, while the evidence above is relevant, far more research needs to be done. Especially, to answer: “Do people experience less intimacy in their current relationships than they did 10 or 20 years ago? Further, do people feel intimate and close to those with whom they are interacting online? To what extent does online context (e.g., public vs. private SNS posts vs. texting) matter in how close people feel to others online?”

How does this all tie together?

In the conclusion of this paper, the authors explain that there is a potential disconnect between the way that we are programmed and the modern world we live in. Referring to the disconnect between our desire to share and receive a response and modern technology. They also further dive into the intimacy process in modern humans and how social media can hijack the process to produce technoference. Lastly, the authors reiterate the importance of further research in this area.

There is plenty of information that I did not go into because at a certain point I would just be rewriting the paper in my own words. And, while that would be a great exercise, I’ll save you, my dear reader, the arduous task of reading through it. If you would like to read more, please see the first citation for reference.

SO WHAT?

Alright, now that we have gotten this information, what can we do with it?

We understand that our brains are hardwired to want to share and receive feedback, and we know that this is best done with those closest to us. Doing this will help us preserve and strengthen those relationships.

A key takeaway is that we are not wrong for being drawn to our phones. It’s not a lack of self-control, but a biological program. This means that we need to hack the program. This can be done at a number of points within the process of our phones grabbing our attention away from our loved ones.

The most obvious, and the most effective, will be to simply have time with our loved ones, without our phones. Making this a routine will be incredibly beneficial. One way that this could look, is to say that every night when we sit down for dinner our phones go into a phone box lock. There is a number online that you can buy. A key benefit is that it takes the need for self-control away. As no one has paid me for a sponsorship, I have just linked the google shop page.

The next step that we can take is to be more self-aware. I know this sounds like some hippy-dippy shit but it really works. There are a number of ways to achieve it (I know I haven’t). The key is to notice when you pick up your phone. Rather than, having your phone be something that you constantly look at, set a reminder every hour to pop up on your phone, “Am I splitting my attention?” If the answer is “yes” put down the phone.

The last step that I will recommend is that we think about when we truly need our phones on us. If there is an emergency someone will call. As such why not leave the phone on the counter when having a conversation with your spouse, child, or other loved one. Emergencies really don’t come up that often, and if they do, why wouldn’t the truth work as a solution:

“Sorry I missed your call an hour ago, but I was having a conversation with my son. How can I help?”

If that script wouldn’t work, then there may be more than a cell phone interrupting your relationships.

Citations

Sbarra, Briskin, J. L., & Slatcher, R. B. (2019). Smartphones and Close Relationships: The Case for an Evolutionary Mismatch. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(4), 596–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619826535

Aagaard, J. (2016). Mobile devices, interaction, and distraction:

A qualitative exploration of absent presence.

Artificial Intelligence & Society, 31, 223–231. doi:10.1007/

s00146-015-0638-z

Dunbar, R. I. M., Marriott, A., & Duncan, N. D. C. (1997).

Human conversational behavior. Human Nature, 8, 231–doi:10.1007/BF02912493

Emler, N. (1990). A social psychology of reputation. European

Review of Social Psychology, 1, 171–193.

Emler, N. (1994). Gossip, reputation, and social adaptation.

In R. Goodman & A. Ben Ze’ev (Eds.), Good gossip (pp.

117–133). Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Hyman, I. E., Boss, S. M., Wise, B. M., McKenzie, K. E., &

Caggiano, J. M. (2009). Did you see the unicycling clown?

Inattentional blindness while walking and talking on a

cell phone. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 597–607.

doi:10.1002/acp.1638

Landis, M. H., & Burtt, H. E. (1924). A study of conversations.

Journal of Comparative Psychology, 4, 81–89.

Lenhart, A., & Duggan, M. (2014). Couples, the internet, and

social media. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://

http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/11/couples-the-internetand-

social-media

McDaniel, B. T., & Coyne, S. M. (2016). “Technoference”: The

interference of technology in couple relationships and

implications for women’s personal and relational wellbeing.

Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5, 85–98.

McDaniel, B. T., Galovan, A. M., Cravens, J. D., & Drouin,

M. (2018). “Technoference” and implications for mothers’

and fathers’ couple and coparenting relationship quality.

Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 303–313.

McDaniel, B. T., & Radesky, J. S. (2018). Technoference:

Parent distraction with technology and associations with

child behavior problems. Child Development, 89, 100–109.

Naaman, M., Boase, J., & Lai, C.-H. (2010). Is it really about

me? Message content in social awareness streams. In

Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer

Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 189–192). New York,

NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

Awesome article!

LikeLike