The Invisible Pandemic (III)

Before I start this post, I would like to say, that this is not medical advice, I am not a doctor, and I don’t choose to play one on the internet.

“An abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behavior.”

Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

It would be a laughable understatement to summarize COVID-19 as simply abnormal, but at the very least that is what it was … abnormal, weird, different.

But what did Coronavirus really do?

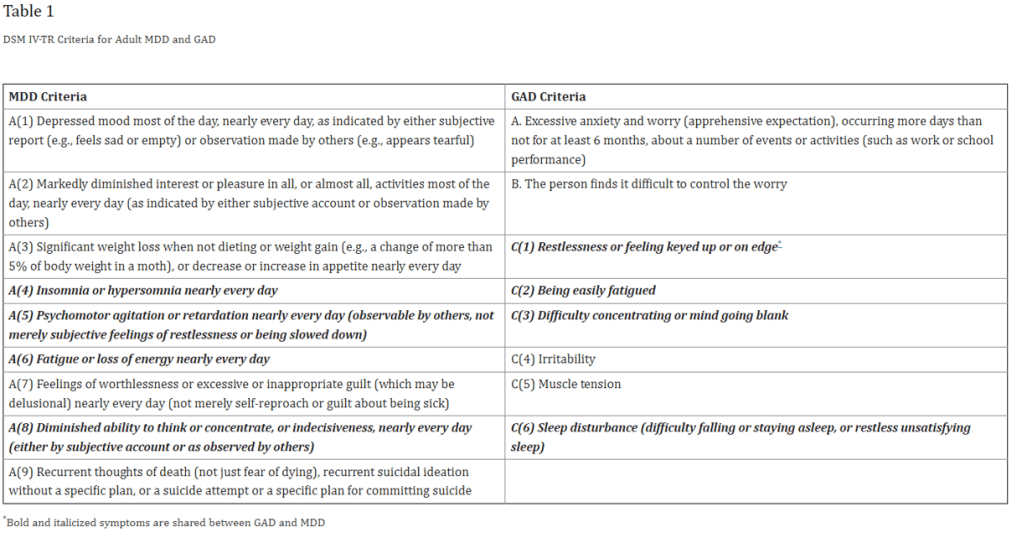

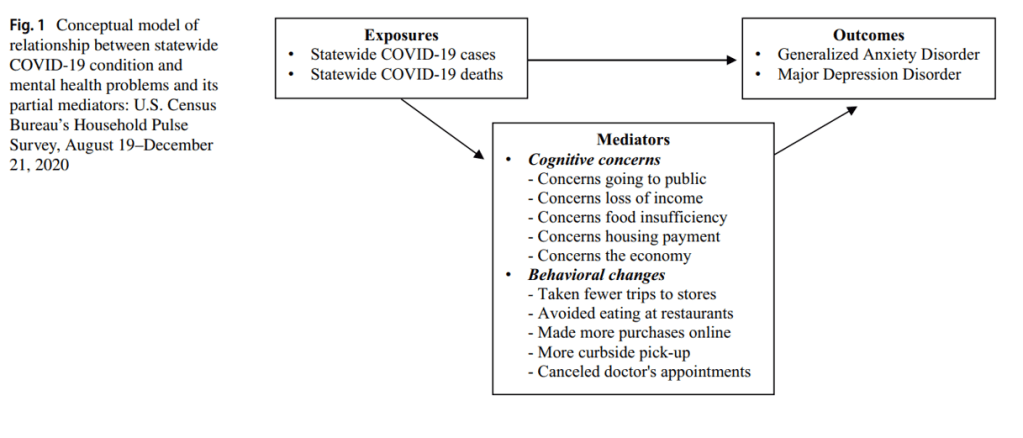

In my last post, I discussed how the Coronavirus Pandemic caused an increase in both Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder. This increase was then used as a benchmark for the less easily measured increases in general mental illness in the world.

University Students in Wuhan China provide a great case study. College is a cesspool for chaos as it is, but the addition of a once-in-a-lifetime event like the Coronavirus pandemic certainly didn’t help. A study by Hafstad et al., explains that mental health problems increased -statistically- significantly from 5.3% (2019) to 6.2% (June 2020).

This jump was most likely caused by the introduction of the Coronavirus Pandemic and lockdowns as it was far and away the largest major event to occur in Wuhan China in that time period. The study explains that “[one] survey was conducted before the confinement and the other was conducted 15–17 days after the start of the confinement. Increases in negative affect and symptoms of anxiety and depression (p-values< 0.001) were observed after 2 weeks of confinement.”

Solutions:

Problems without solutions are a great way to fall deeper into this trap of anxiety and depression. I was listening to a podcast while driving and an idea struck me like a rock; Depression and anxiety are signs that we need to change something.

To be clear, “struck me like a rock” means that someone said it and it hit me. In my infinite wisdom, I just cannot seem to remember who or where.

When we have an infection, we don’t assume that something is innately wrong, we go to the doctor and take antibiotics. We know that there is a bacterium making us sick and that we need to help our bodies fight it off. Why, then, do we assume that there is something inately wrong with us when we are depressed or anxious? Is a sickness of the mind not still a sickness to be addressed?

The Question Remains, How?

There are a few steps, but the first step is the identification of the culprits. Bhattacharjee et al., describes the 5 most at risk groups for mental illness during the Coronavirus Pandemic:

- “Elderly People”

- “Professionals,” specifically those with “immense mental stress regarding their job security.”

- “Healthcare Professionals”

- “Children and teenagers”

- “People with past and family psychiatric history”

These people have a lot in common, the first is that they are often more susceptible to fear of illness (for good reason), while the second is that they often are lacking in strong social networks.

A few other risk factors for depression can be seen on the National Institute of Mental Illness’ website:

- “Major life changes, trauma, or stress”

- “Certain physical illnesses and medications”

Anxiety also has similar risk factors that can be seen on the Mayo Clinic’s website:

- “Trauma”

- “Stress due to an illness”

- “Stress buildup”

- “Personality”

- “Drugs or alcohol”

Of course, there are more risk factors, but these paint a good picture. If we want to lower our chances of increased anxiety and depression in a life-changing event like Coronavirus, we need to remove as many risk factors as possible.

At this point, there are no guarantees, but we can definitely rig the game to our favor. The three factors that are most important and within our control are stress buildup, physical illness, and social network strength.

I cannot stress the challenge of controlling these things enough. Nevertheless, these things are within our control. And while I have in no way been successful at applying all of these things, I have read much of the research, and seen success while implementing it in my own life.

These tips matter regardless of whether or not there is a pandemic raging across the globe. And like most things in life, these work far better as a preventative measure than a reactive one.

Stress Buildup

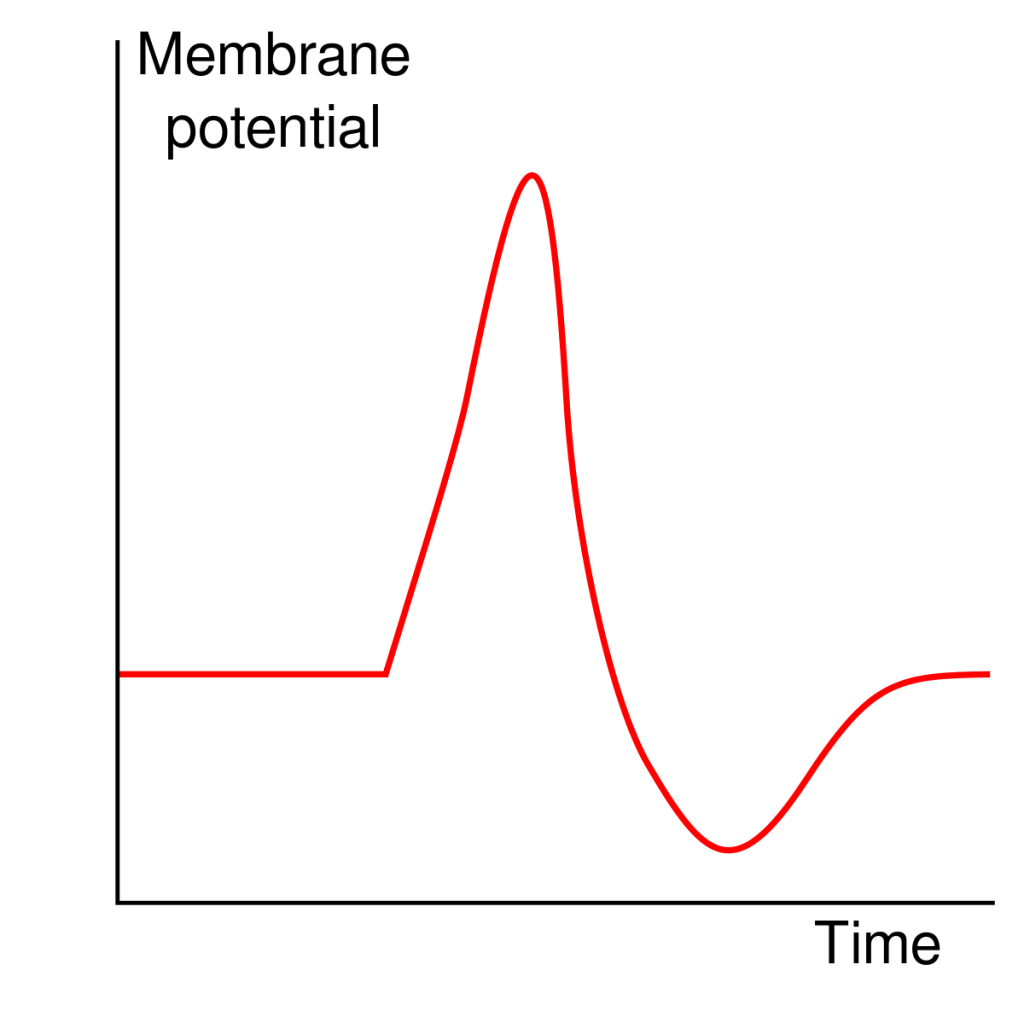

Stress is pervasive in our lives and is not something that we should strive to get rid of altogether. It can help to motivate us and get our butts moving in the right direction when we need it. (See eustress from tim.blog) It should not, however, be ever-present and always building.

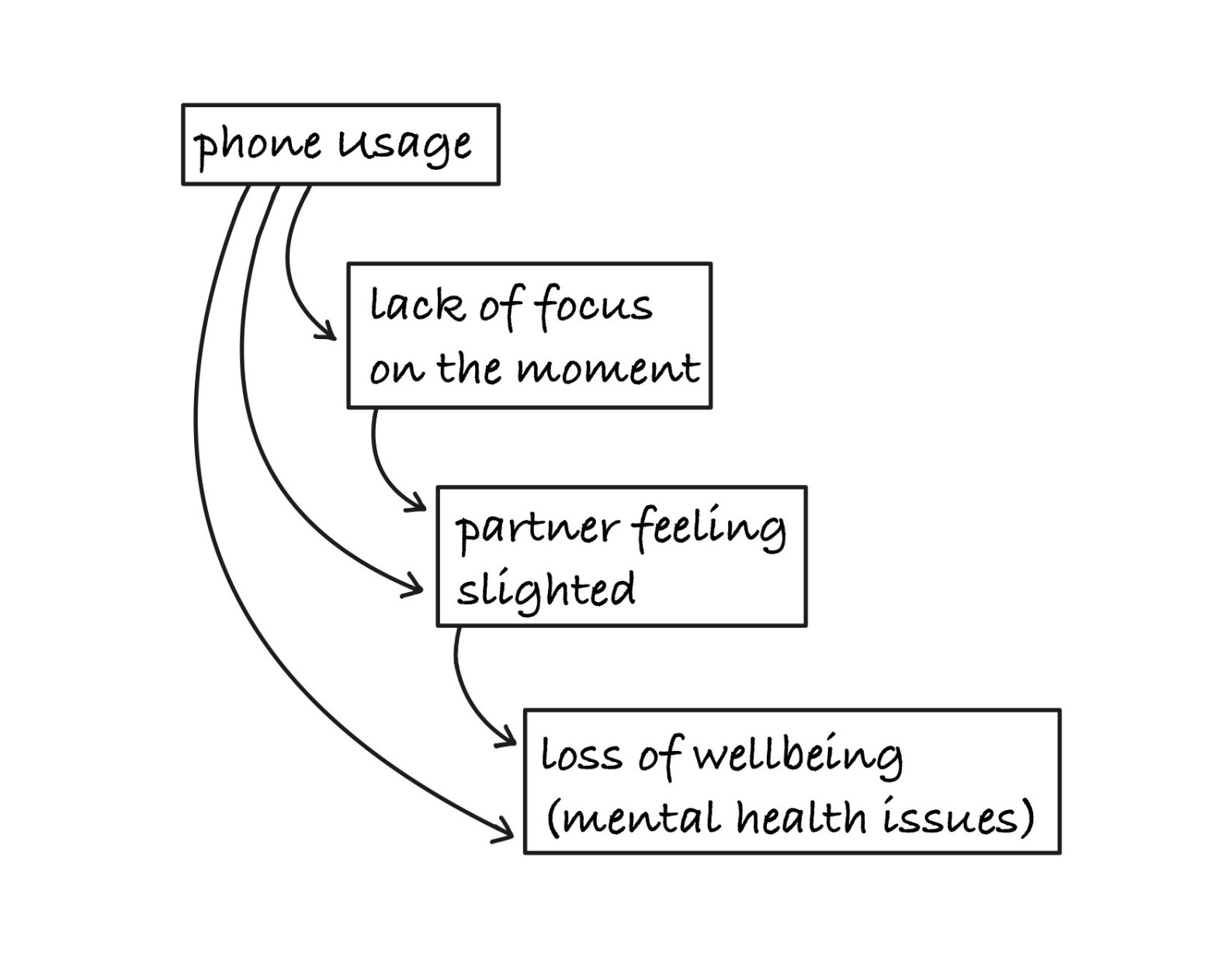

The first step to breaking out of the cycle of growing stress is to find where the stress is coming from. There are a number of sources, as well as blogs written on this topic, but I would wager that most people when they really think about it, know where the stress is coming from.

Once the root cause is narrowed down, say your job, it’s easy. Quit your job.

… I wish.

For some people, it can be that simple, but for most of us, if you could have quit then you would have quit. In place of this “easy” and often impractical fix, there are a number of much more attainable steps.

If you are in a bad situation, be it at work or in a relationship, begin to work your way out. If it’s work, start applying to other jobs. If it’s a friendship, begin to expand your network through sports or other social events. Websites like https://www.meetup.com and https://www.reddit.com are a great way to find communities of like-minded people.

Another great way to reduce stress is through mediation. There are countless studies explaining the reasoning both psychiatrically and physiologically. A great conversation with Sam Harris (Neuroscience Ph.D.), Daniel Goleman (Ph.D.), and Richard J. Davidson (Psychology and Psychiatry Ph.D.) that goes into some of the science behind mediation can be found here.

Many people who pride themselves on valuing research consider meditation to be this weird hippy-dippy shit. I would challenge them to actually analyze the research and try it before solidifying their opinions.

I have found that the Waking Up App (Sam Harris) is very good as an introductory course for me because it provides a very logic-based non-religious approach. A hard, intensely focused workout routine can also provide similar benefits of decreased stress.

Physical Illness

When I moved to Chicago, earlier this summer, I stopped eating as healthily and exercising as much. I went from lots of fresh food and supplements to fast food and takeout because it was easier while moving. My workout routine also changed from working out at least one hour a day, six days a week, to two total hours a week. Following my brilliance, I caught a cold and it stuck with me for over two weeks.

After, a major move the last thing that I wanted to do was isolate. I was unsure of myself as it was, let alone being forced to stay in and not meet new people. It also doesn’t leave the best impression, when you work from home for the first two out of three weeks at a new, in-person, job.

It doesn’t matter if you get a bad cold, have terrible back pain, or catch COVID-19. All of these things can play a role in dampening your spirits and worrying you. Because of this, it’s important to maintain a strong immune system and a healthy body.

In Italy, a survey study analyzed the correlation of weekly activity to weekly mental health ratings. In this study, Maugeri et al. discovered that there was a strong positive correlation between minutes worked out per week and mental well-being. This data further suggested, that one of the many factors contributing to people’s poor mental health during the Coronavirus, was that average weekly activity dropped from 2429 min/week to 1577 min/week.

Social Network Strength

Maintaining valuable relationships is far more important than building new ones. I make it a point to try to keep in contact with my close friends, even after moving halfway across the country. I often fail, but having a conversation with a good friend, after months always leaves me rejuvenated.

The highlight of my week since moving is often an hour-long conversation with an old friend. Just catching up and remembering that people share your values and experiences does wonders for making sure that you stay mentally healthy during both good and bad times.

A key reason that quarantining was so hard on so many people, was because it cut us off from our support systems. Having friends and family is a key part of how we cope and thrive. Thousands of banal platitudes aside, cherishing those close to you matters. If you’re interested in learning more about the value of those close relationships, my entire series (Impacts of Interpersonal Relationships) can be found here.

Key Takeaways

Three steps to help your odds of staying mentally strong during a pandemic, or just during the regular chaos of life:

- Reduce your Stress, through analyzing your day-to-day and meditating.

- Improve your physical health, through exercise.

- Improve your social network by expanding it and valuing those relationships closest.

Hopefully, this provides some insight into some ways to better our lives and increase the odds of living a more contented life. These are some things that have definitely helped me over the last few years.

I know that these all seem quite simple, but at the end of the day, the simple steps are the most effective, and the most attainable, for the average person (whatever that means).

To view all of my research for this post, as well as the previous posts for the Invisible Pandemic, you can visit my Invisible Pandemic Hub @ Kahana.co by following this link.